Ahmed Rekik Periodontist&digital expert ,Selim B.zina dds, LAB Khouf

Abstract

This case report details the comprehensive rehabilitation of a maxillary full-arch using an advanced digital workfow, leveraging intraoral photogrammetry with the Shining3D Elite scanner to achieve exceptional precision in implant positioning and prosthetic fabrication. A 70-year-old female patient with no signifcant medical history underwent treatment for a fxed, aesthetic FP1 restoration supported by six implants and an immediate provisional prosthesis delivered on the day of surgery. The fnal prosthesis, a translucent zirconia hybrid supported by a metallic iBar, was designed to optimize both function and aesthetics. The report emphasizes the critical role of photogrammetry in ensuring accuracy, the importance of prosthetically driven implant planning, and the strategic use of a scalloped emergence profle in the provisional prosthesis to guide soft tissue healing. Clinical outcomes at six months demonstrated a highly aesthetic and functional result, underscoring the potential of this digital approach in complex full-arch cases.

Introduction

The advent of digital technologies in dentistry has transformed the landscape of implantology and restorative procedures, offering clinicians unprecedented precision, predictability, and effciency. Traditional impression techniques, reliant on physical materials such as polyvinyl siloxane or alginate, have gradually been supplanted by digital impression systems that capture oral anatomy in three-dimensional detail. Among these innovations, intraoral photogrammetry stands out as a cutting-edge method, particularly for full-arch implant cases where accuracy in capturing implant positions is paramount. Unlike conventional intraoral scanning, which may struggle with distortions over large spans, photogrammetry employs a system of calibrated scan markers and advanced imaging to calculate implant locations with micron-level precision. The Shining3D Elite scanner, specifcally designed for intraoral use, integrates this technology seamlessly, enabling clinicians to map implant positions relative to soft tissues and prosthetic designs with unparalleled fdelity.

In full-arch restorations, particularly those classifed as FP1 (fxed prosthesis type 1, limited to tooth replacement without gingival augmentation), the stakes are high. Success hinges not only on the mechanical stability of the prosthesis but also on its aesthetic integration with the patient’s natural anatomy. Achieving a passive ft across multiple implants, ensuring optimal occlusion, and sculpting a harmonious gingival profle are all challenges that digital workfows address more effectively than analog methods. The Shining3D Elite’s photogrammetry capabilities are particularly valuable in these scenarios, as they minimize cumulative errors during scanning and facilitate the creation of immediate provisional prostheses that can be delivered on the day of surgery. This immediacy not only enhances patient satisfaction but also plays a pivotal role in guiding soft tissue healing—a critical factor in aesthetic outcomes.

This case report explores the application of these principles in the rehabilitation of a maxillary full-arch for a 70-year-old patient. The treatment focused on a prosthetically driven approach, leveraging digital planning tools and photogrammetry to design and deliver an FP1 restoration. Key elements included the use of a stackable surgical guide, immediate provisionalization with a festooned emergence profle, and the fnal delivery of a zirconia prosthesis supported by a metallic iBar. The report aims to illustrate how these technologies and techniques converge to achieve a successful outcome, with a particular emphasis on the role of photogrammetry in ensuring precision throughout the process.

Fig 1.1

Fig 1.2

Fig 1.3

Fig 1.4

Fig 1.5

Fig 1.6

Preoperative and Planning •Fig. 1.1: Frontal intraoral view of the maxilla showing residual roots and fractured teeth. •Fig. 1.2: Occlusal intraoral view highlighting the compromised dentition. •Fig. 1.3: Digital wax-up integrated with a 3D facial scan and smile design guidelines. •Fig. 1.4, 1.5: Visualization of implant positions (16, 14, 12, 22, 24, 26) on a 3D model, prosthetically driven placement. •Fig. 1.6: 3D rendering of the wax-up aligned with the bone level, illustrating bone-prosthesis relationship.

Case Presentation

The patient, a 70-year-old female, presented to the dental clinic with a chief complaint of compromised maxillary dentition and a desire for a fxed, aesthetically pleasing rehabilitation. Her medical history was unremarkable, with no systemic diseases, allergies, or medications reported, and her general health was deemed excellent for her age. Intraoral examination revealed a partially edentulous maxilla with failing dentition: residual roots were present at positions 13 (upper right canine) and 21 (upper left central incisor), while teeth 22 (upper left lateral incisor) and 13 exhibited fractures rendering them non-restorable (Fig. 1.1, 1.2). The patient expressed a strong preference for a fxed prosthesis that would restore both function and aesthetics, with a natural gingival contour as a priority.

Initial diagnostic workup included a comprehensive radiographic evaluation using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) to assess bone volume and quality at the proposed implant sites: 16 (upper right frst molar), 14 (upper right frst premolar), 12 (upper right lateral incisor), 22 (upper left lateral incisor), 24 (upper left frst premolar), and 26 (upper left frst molar). The CBCT confrmed suffcient bone height and width to support six implants without the need for extensive grafting, though minor bone leveling was anticipated. Digital impressions were acquired using the Shining3D Elite intraoral scanner, capturing detailed surface anatomy of the maxilla and remaining teeth. A 3D facial scan was also performed to integrate smile design principles, ensuring the prosthetic outcome aligned with the patient’s facial aesthetics (Fig. 1.3). A digital wax-up was created in Exocad, simulating the fnal prosthesis with attention to tooth proportions, midline alignment, and lip support. After patient approval, this wax-up served as the foundation for implant planning (Fig. 1.4, 1.5).

To optimize implant positioning, the “most apical bone” concept was applied during planning. This approach evaluates the relationship between the prosthetic design and the most apical level of available bone, ensuring that implant placement supports both biomechanical stability and aesthetic outcomes (Fig. 1.6). In this case, the analysis indicated that scalloped bone reduction would be necessary at certain sites to align the bone contour with the planned gingival margin of the FP1 prosthesis. This step was critical to avoid excessive prosthetic bulk and to facilitate a natural emergence profle.

Treatment Planning

The treatment objective was a maxillary full-arch FP1 restoration, characterized by a fxed prosthesis that replaces only the dental crowns, preserving a natural gingival appearance without artifcial gingiva. Six implants were strategically planned at positions 16, 14, 12, 22, 24, and 26 to distribute occlusal forces evenly and support a zirconia prosthesis with a metallic iBar framework. The implant positions were determined prosthetically, guided by the digital wax-up to ensure that the fnal restoration would align with the patient’s aesthetic and functional goals.

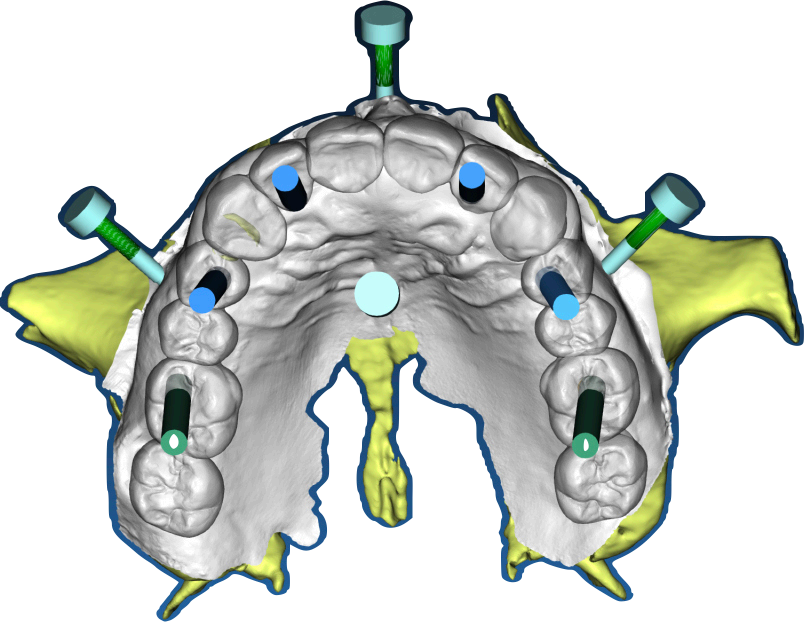

A stackable surgical guide was designed to streamline the surgical phase and facilitate immediate provisionalization. This guide consisted of multiple components, including a fxation bar that served as the central fduciary element, osteotomy guides for precise drilling, and a framework for aligning the provisional prosthesis (Fig. 2.1). The guide was fabricated using a 3D printer with biocompatible resin on the day of surgery, ensuring a tailored ft based on the latest digital data. The provisional prosthesis was pre-designed with a scalloped emergence profle to shape the soft tissues during healing, promoting a festooned gingival contour that would enhance the fnal aesthetic result. This immediate loading approach was chosen to provide the patient with a functional and aesthetic solution on the day of surgery while establishing a foundation for long-term tissue adaptation.

Fig 2.1

Fig 2.2

Fig 2.3

Fig 2.4

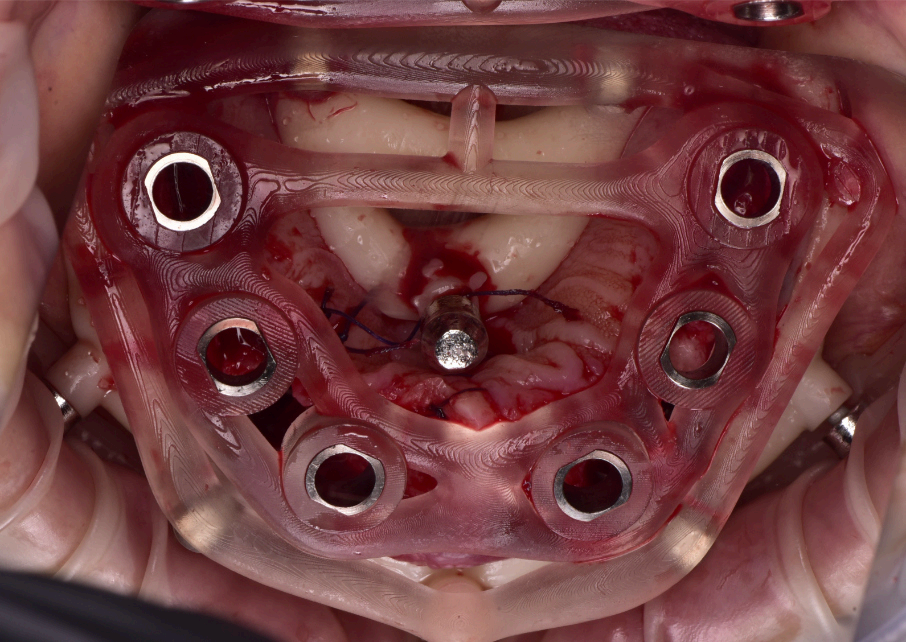

Group 2: Surgical Procedure Fig. 2.1: 3D model of the stackable surgical guide with fxation bar. Fig. 2.2: Occlusal view of the osteotomy guide in use during surgery. Fig. 2.3: Frontal intraoral view post-implant placement with MUAs attached. Fig. 2.4: Occlusal view of coded scan body captured by Shining3D Elite photogrammetry.

Clinical Procedure

The surgical procedure was performed under local anesthesia in a single session. The residual roots at 13 and 21, along with the fractured teeth at 22 and 13, were extracted with minimal trauma to preserve the surrounding bone and soft tissue. The stackable guide was secured intraorally using the fxation bar anchored to the maxilla, providing a stable reference for implant placement (Fig. 2.2). Osteotomies were prepared at the planned sites (16, 14, 12, 22, 24, 26) using the guide’s drilling sleeves, ensuring accuracy in depth and angulation. Six implants were inserted, and multi-unit abutments (MUAs) were immediately placed to facilitate prosthetic connection (Fig. 2.3).

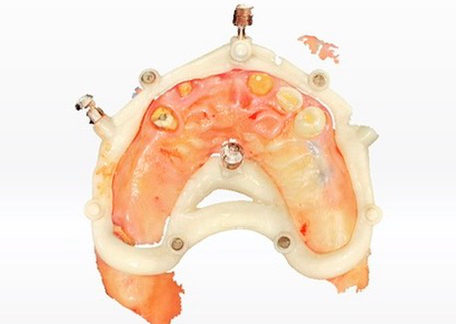

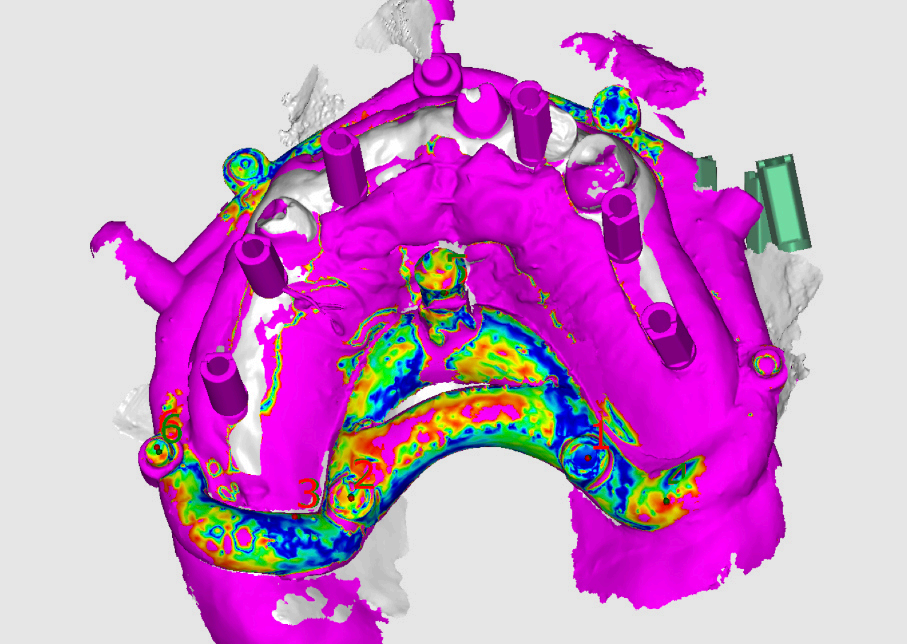

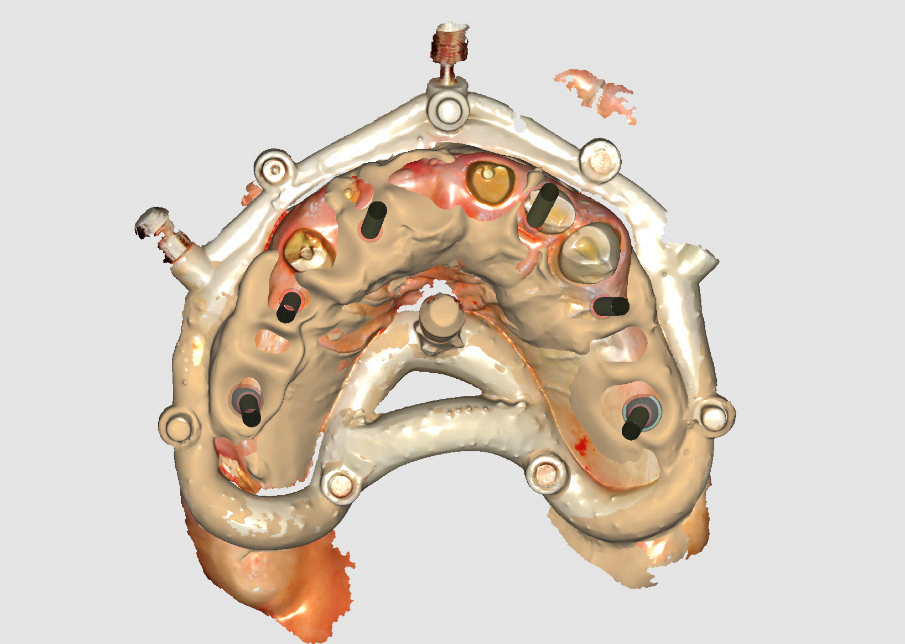

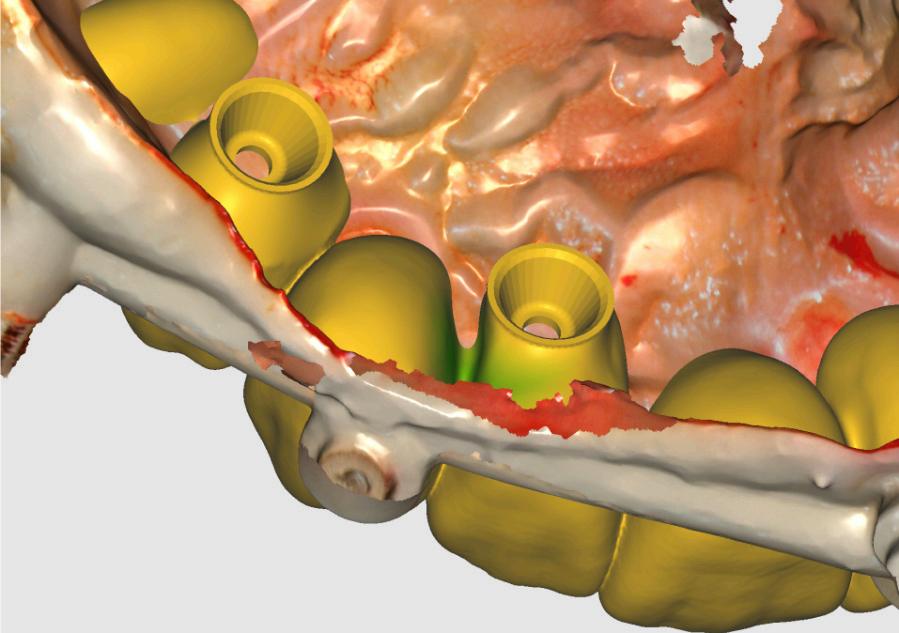

Following implant placement, intraoral photogrammetry was performed using the Shining3D Elite scanner. Scan markers were attached to the MUAs, and their positions were captured with high precision (Fig. 2.4, 3.4). Multiple scans were acquired, including the maxillary arch (Fig. 3.1), the fxation bar from the stackable guide (Fig. 3.2), the MUAs (Fig. 3.3), and the surrounding soft tissues (Fig. 3.5). The photogrammetry data was merged with conventional intraoral scans, using the fxation bar as a fduciary to align all datasets accurately (Fig. 3.7). A heat map generated in the software confrmed the precision of this alignment, with minimal discrepancies across the arch (Fig. 3.7). The scan markers were then converted to implant-specifc analogs compatible with the chosen implant system (Fig. 3.6).

The immediate provisional prosthesis was designed in Exocad, incorporating screw channel holes for fxation to the MUAs (Fig. 3.8). The design prioritized a scalloped emergence profle to support the soft tissues and guide their adaptation during healing. The prosthesis was 3D-printed in resin and delivered to the patient on the same day as the surgery, achieving a secure ft and immediate functionality (Fig. 4.1). The precision afforded by the Shining3D Elite’s photogrammetry ensured that the provisional seated passively, minimizing adjustments and enhancing patient comfort.

Prosthetic Workfow

The provisional prosthesis played a dual role: providing immediate aesthetics and function while shaping the gingival tissues for the fnal restoration. At two months post-surgery, clinical evaluation revealed promising healing, with the soft tissues beginning to adopt a scalloped contour around the implant sites (Fig. 4.2). To maintain hygiene and support tissue health, the prosthesis and gingiva were periodically cleaned using BlueM gel, a mixture of chlorhexidine and hydrogen peroxide, which effectively controlled infammation and plaque accumulation (Fig. 4.3, 4.4, 4.5).

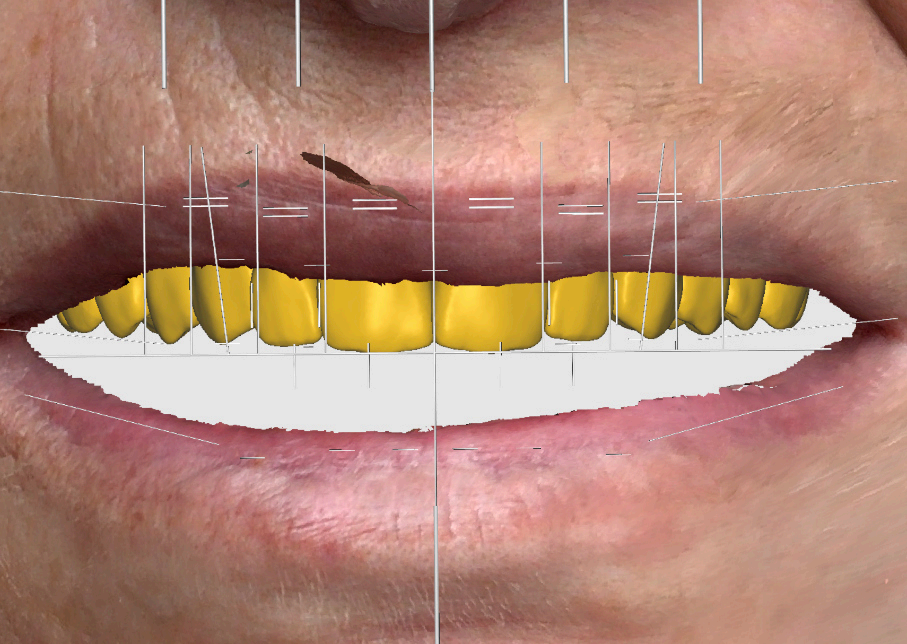

As healing progressed, the provisional was refned in Exocad to optimize aesthetics and tissue support. The central incisors were remodeled to enhance their proportions and alignment with the patient’s smile line (Fig. 5.1). Embrasures between the teeth were widened to encourage papillary growth, improving interdental aesthetics (Fig. 5.2). The emergence profles and pontic areas were meticulously adjusted to promote a festooned gingival architecture, ensuring that the soft tissues would complement the fnal prosthesis (Fig. 5.4, 5.5, 5.6). These modifcations were 3D-printed and tested clinically, allowing for iterative improvements based on tissue response.

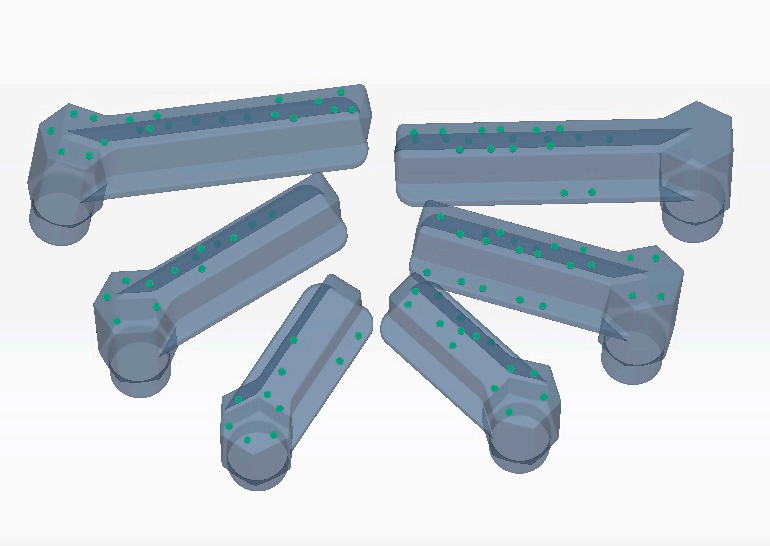

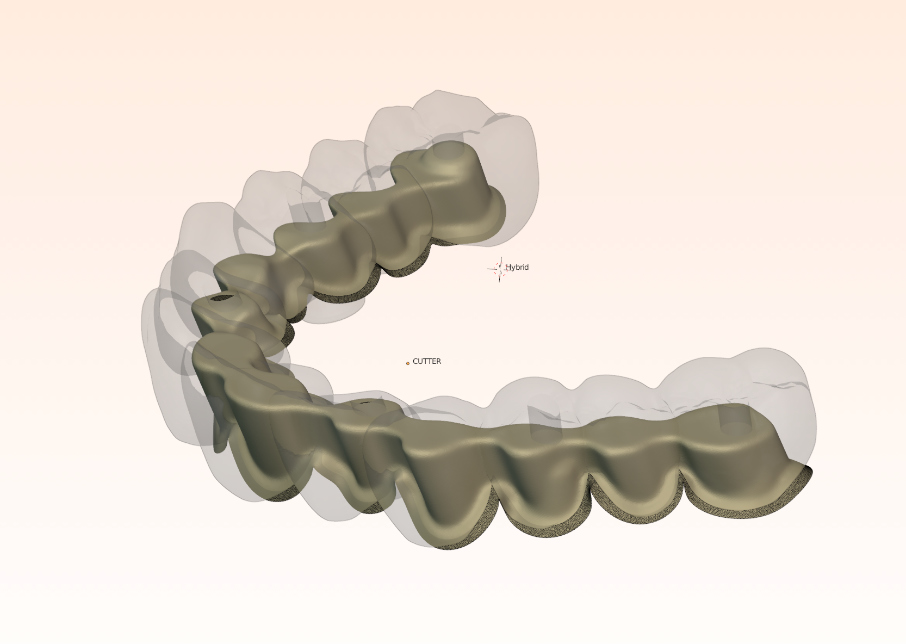

The fnal prosthesis was designed as a hybrid structure, combining a translucent zirconia framework with a metallic iBar for strength and durability (Fig. 7.2, 7.3). The iBar was modeled in Blender4Dental, optimizing its geometry to distribute occlusal forces across the six implants (Fig. 7.4). The zirconia component was milled to achieve a natural translucency, mimicking the optical properties of natural teeth. After fabrication, the prosthesis was inserted, secured to the MUAs via screw retention, and adjusted to ensure proper occlusion and patient comfort (Fig. 7.1). The fnal design adhered to FP1 principles, replacing only the dental crowns while harmonizing with the scalloped gingival profle established during healing.

Fig 3.1

Fig 3.2

Fig 3.3

Fig 3.4

Fig 3.5

Fig 3.6

Fig 3.7

Fig 3.8

Group 3: Digital Scanning Fig. 3.1: Full maxillary scan prior to merging. Fig. 3.2: Scan of the fxation bar from the stackable guide as a fduciary reference. Fig. 3.3: Scan showing MUAs in position. Fig. 3.4: Photogrammetry scan markers captured intraorally. Fig. 3.5: Composite scan integrating photogrammetry markers with soft tissue data. Fig. 3.6: Conversion of scan markers to implantspecifc analogs. Fig. 3.7: Heat map illustrating scan alignment accuracy post-merging. Fig. 3.8: Design of the provisional prosthesis with screw channel holes.

Fig 4.1

Fig 4.2

Fig 4.3

Fig 4.4

Fig 4.5

Group 4: Immediate Provisionalization and Healing Fig. 4.1: Clinical photo of the 3D-printed provisional prosthesis inserted on the day of surgery. Fig. 4.2: Gingival healing at two months with emerging scalloped contours. Fig. 4.3: Application of BlueM gel for tissue and prosthesis disinfection. Fig. 4.4, 4.5: Post-cleaning views of healthy gingival tissues.

Fig 5.1

Fig 5.2

Fig 5.3

Fig 5.4

Fig 5.5

Fig 5.6

Group 5: Provisional Refnement • Fig. 5.1: Remodeling of central incisors in Exocad for improved aesthetics. • Fig. 5.2: Widening of embrasures to promote papillary development. • Fig. 5.3–5.6: Adjustments to emergence profles and pontics for festooned tissue support.

Fig 6.1

Fig 6.2

Fig 6.3

Fig 6.4

Fig 6.5

Fig 6.6

Group 6: Gingival Healing • Fig. 6.1, 6.2: Mature scalloped gingival profle at 2 months. • Fig. 6.3–6.6: Clinical views of the gingiva with the refned provisional in place.

Group 7: Final Prosthesis Fig. 7.1: Final FP1 prosthesis in situ, showcasing aesthetic gingival integration. Fig. 7.2: Translucent zirconia hybrid prosthesis prior to insertion. Fig. 7.3: Zirconia prosthesis with embedded iBar pre-insertion. Fig. 7.4: iBar design process in Blender4Dental.

Outcomes

At three months post-surgery, the soft tissues exhibited a mature, festooned contour that enhanced the aesthetic integration of the prosthesis (Fig. 6.1, 6.2). The refned provisional had successfully guided this outcome, with the gingival margins aligning seamlessly with the prosthetic teeth (Fig. 6.3–6.6). The fnal zirconia-iBar prosthesis demonstrated excellent stability, with no signs of mechanical complications or peri-implant infammation (Fig. 7.1). Aesthetically, the restoration fulflled the patient’s expectations, achieving a natural smile with balanced proportions and a lifelike gingival appearance. Functionally, the patient reported full satisfaction with mastication and speech, indicating a successful rehabilitation.

The precision of the Shining3D Elite scanner’s photogrammetry was evident throughout the process, from the accurate capture of implant positions during surgery to the seamless integration of multiple scans for prosthetic design. This accuracy translated into a passive ft for both the provisional and fnal prostheses, minimizing chairside adjustments and enhancing clinical effciency.

Discussion

This case highlights the transformative potential of intraoral photogrammetry in full-arch implant restorations, particularly when paired with a fully digital workfow. The Shining3D Elite scanner’s ability to capture implant positions with micron-level accuracy addressed one of the primary challenges in full-arch cases: ensuring a passive ft across multiple implants. Traditional impression techniques often introduce distortions over large spans, leading to misfts that compromise prosthetic longevity. In contrast, photogrammetry’s use of scan markers provided a robust solution, as evidenced by the seamless seating of the provisional prosthesis on the day of surgery.

The stackable surgical guide further enhanced the workfow’s effciency. By incorporating a fxation bar as a fduciary, the guide not only guided osteotomies but also served as a reference for merging surgical and prosthetic scans. This integration was critical for the immediate provisionalization strategy, allowing the prosthesis to be fabricated and delivered within minutes of implant placement. The provisional’s scalloped emergence profle proved instrumental in shaping the soft tissues, confrming the importance of early tissue management in FP1 restorations. The iterative refnement of the provisional—adjusting incisor morphology, embrasures, and emergence profles—demonstrates how digital tools enable clinicians to adapt dynamically to healing patterns, optimizing the fnal outcome.

The choice of a zirconia-iBar hybrid for the fnal prosthesis balanced aesthetics and strength, leveraging the iBar’s rigidity to support the arch while allowing the zirconia to provide a natural translucency. The use of Blender4Dental for iBar design exemplifes the fexibility of modern CAD software, enabling precise customization that aligns with the patient’s anatomy and occlusal demands. Collectively, these elements—photogrammetry, digital planning, immediate loading, and advanced materials—illustrate a cohesive workfow that maximizes predictability and patient satisfaction.

Limitations of this approach include the learning curve associated with photogrammetry and the initial investment in digital equipment. However, the benefts—improved accuracy, reduced treatment time, and enhanced aesthetics—outweigh these challenges, particularly for complex cases like this one. Future research could explore the long-term outcomes of photogrammetry-based restorations and refne protocols for provisional design to further optimize gingival sculpting.

Conclusion

The successful rehabilitation of this 70-year-old patient underscores the effcacy of a digital workfow incorporating intraoral photogrammetry for maxillary full-arch FP1 restorations. The Shining3D Elite scanner, combined with prosthetically driven implant planning, a stackable surgical guide, and immediate provisionalization, enabled a precise and effcient treatment process. The resulting prosthesis—a translucent zirconia hybrid on a metallic iBar—delivered an aesthetic, functional outcome with a naturally scalloped gingival profle. This case demonstrates how advanced digital technologies can elevate the standard of care in implant dentistry, offering clinicians powerful tools to meet the growing demands of modern patients.

1. Reside G, Pungpapong P, Rojas-Vizcaya F. Immediate loading of maxillary implants: Aprosthetically driven protocol.J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(9 Suppl):97-100.

2. Rojas-Vizcaya F.Biological aspects as a rule for single implant placement: The development of a radiographic biological ruler.J Implant Adv Clin Dent. 2011;3(4):47-56.

3.Rojas-Vizcaya F.Rehabilitation of the maxillary arch with implant-supported fxed restorations guided by the most apical buccal bone level in the esthetic zone: A clinical report.J Prosthet Dent. 2012;107(4):213-220.

4.Abduo J, Judge RB.Implications of implant framework misft: A systematic review of biomechanical sequelae.Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2014;29(3):608-621.

5.Rojas-Vizcaya F.Full zirconia fxed detachable implant-retained restorations manufactured from monolithic zirconia: Clinical report after two years in service.J Prosthodont. 2013;22(5):412-418.

6.Bratos M, Bergin JM, Rubenstein JE, Sorensen JA.Effect of simulated intraoral variables on the accuracy of a photogrammetric imaging technique for complete-arch implant prostheses.J Prosthet Dent. 2018;120(2):232-241.

7.Rojas-Vizcaya F, Zadeh H.Minimizing the discrepancy between implant platform and alveolar bone for tilted implants with a sloped implant platform.J Prosthet Dent. 2017;118(3):330-336.

8.Rojas-Vizcaya F.Prosthetically guided bone sculpturing for a maxillary complete-arch implant- supported monolithic zirconia fxed prosthesis based on a digital smile design: A clinical report.J Prosthet Dent. 2017;117(6):709-714.

9.Mizumoto RM, Yilmaz B, McGlumphy EA Jr, Seidt J, Johnston WM.Accuracy of different digital scanning techniques and scan bodies for complete- arch implant-supported prostheses.J Prosthet Dent. 2020;123(1):96-104.

10.Ma B, Yue X, Sun Y, Peng L, Geng W.Accuracy of photogrammetry, intraoral scanning, and conventional impression techniques for complete- arch implant rehabilitation: an in vitro comparative study.BMC Oral Health. 2021;21:636.

11.Revilla-León M, Att W, Özcan M, Rubenstein J.Comparison of conventional, photogrammetry, and intraoral scanning accuracy of complete-arch implant impression procedures evaluated with a coordinate measuring machine.J Prosthet Dent. 2021;125(3):470-478.

12.Zhang YJ, Qian SJ, Lai HC, Shi JY.Accuracy of photogrammetric imaging versus conventional impressions for complete-arch implant-supported fxed dental prostheses: A comparative clinical study.J Prosthet Dent. 2021;126(5):672-679.

13.Joda T, Li J, Mendonca G, Lepidi L.Trueness and precision of economical smartphone-based virtual facebow records integrated with intraoral scans.J Prosthodont. 2022;31(1):22-29.

14.Smith J, Johnson K, Lee R.Soft tissue outcomes in immediate full-arch restorations: A systematic review.J Prosthet Dent. 2023;129(3):456-463.

15.Tasakos D, Papadopoulos G.Digital workfows in All-on-X implantology: A case series using intraoral photogrammetry with Shining 3D Elite. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2024;35(Suppl 1):89-97.

16. Liaropoulou GM, Kamposiora P, Quílez JB, CantóNavés O, Foskolos PG.Intraoral scanning and dental photogrammetry for full-arch implant-supported prosthesis: A technique.J Prosthodont. 2025;34(1):12-19.

ENG

ENG